Green Spaces, the city public parks action group, announced this week that the derelict Cranford Baths on the banks of the East Patterson River, a dozen miles north of the city center, will soon be converted into a public park and memorial space to open next year.

Green Spaces, the city public parks action group, announced this week that the derelict Cranford Baths on the banks of the East Patterson River, a dozen miles north of the city center, will soon be converted into a public park and memorial space to open next year.

The news comes as a relief to residents of nearby suburban Thorn Grove, who have long considered the Baths a dangerous eyesore: the shell of a colonial-style house, the former main office, borders acres of overgrown fields littered with rubbish. Other facilities on the grounds stand half-demolished, while the riverside baths sit stagnant, a temporary fence erected at the central causeway and nets stretched across the open water. A lack of access consistently discourages developers from buying up the site, which remains in the hands of the Thorn Grove Public Properties and Acquisitions Board for now.

It is perhaps difficult to imagine after eight decades of decay, but the site’s current ill repute stands in stark contrast to its previous life as an illustrious health resort and public space at the turn of the last century. Local historian Brian Ramirez explains: “Bathers would approach the baths by an L-shaped causeway jutting out into the river. The water filled the enclosed baths while the current of the river supplied fresh water. Horses pulled rented individual bathing boxes with wheels into the enclosed space”. First reserved as a playground for the elite, the Baths grew in popularity by the year until the Great Depression, serving as a “traditional focal point not only for the community here but also people from the city”, according to Ramirez.

The Cranford Baths Leisure and Regeneration Center was the brainchild of Buckley Cranford, a successful entrepreneur whom the Journal-American described as “a boisterous fellow whose light spirit and prolonged laughter spreads a jovial air about his person.” Cranford, the heir of a New Jersey dairy family, had served as a land surveyor in the Civil War, but found the soldier’s life disagreeable: “War is frightful,” he wrote a friend, “as it is utterly boring.”

Cranford was not without his patriotic side, however. He proudly displayed in his office a letter to his mother Constance, from Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, announcing the death of his only brother at Gettysburg (the letter now resides in the Rincher Museum of Municipal History).

After the war, Buckley was given family permission to indulge his entrepreneurial spirit. He invested in one of the first recreational hot air balloon companies and opened an insurance firm during the 1870’s. Both were ringing successes, but Cranford reportedly tired easily of the nuts-and-bolts side of his ventures. “In a profound malaise” by the second half of the decade, he waved away a seat on the City Council and, after marrying in 1876, took to lengthy sojourns in the country.

It was on one of these visits that Cranford laid his eyes on the future site of his Baths. Cranford had recently visited a health resort in Connecticut, and inspiration struck him. He attests, in a pamphlet advertising the Baths from 1892, “I knew straight away of this site’s restorative power. In its waters, all maladies upon me lifted; all jangling anxieties left me, leaving a blissful consort.”

The site was indeed already well-known as an untouched natural enclave when Cranford visited. The citizens of nearby Thorn Grove, population two hundred and sixty-four, carried a reputation for excellent health. At the time, recorded rates of polio and croup infections were effectively zero. Ramirez doesn’t doubt the positive effect such a reputation had on local business, but he is doubtful of the evidence: “This is back when the Church still kept the records, mind you”.

Mr. Cranford spent a year wrangling for control of the land with a local farmer; a settlement of $8,000 (roughly $150,000 today for ten acres, considered scandalously overpriced at the time) finally landed the site in his lap. The entrepreneur’s influence with City Council and state officials ensured Health Board licensing passed without incident, and the Baths opened to great fanfare on July 3, 1880 (Independence Day falling on a Sunday that year, Mrs. Eulalie Cranford forbade her husband to work on the Sabbath).

Cranford Baths Staff Day, May, 1906

While the Baths were exclusively for gentlemen, the grounds were open to all, boasting one of the nation’s first tennis courts and providing a meticulously cultivated retreat amidst what was at the time still dense forest. Later, sitting pools and a bandstand were installed. A special trolley from Jefferson Station to the sleepy riverside community was opened in 1904, with tea and biscuits served en route (earning it the nickname the “Kettle Express”). The first Saturday of every spring and summer month was a free-admission Open Day, a staple of any area child’s weekend activities.

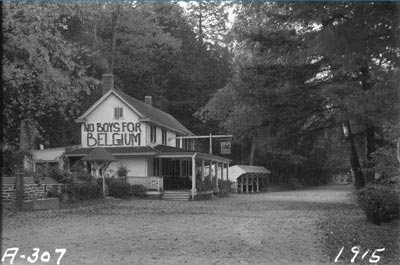

While the Baths became a popular local landmark, Cranford himself became known as a bit of an eccentric. Of German descent on his mother’s side, he vehemently opposed American intervention in World War I, and beginning in 1915 painted his political views on the side of the main office building. The large, crudely written slogans read, for example, “WHILE DOUGH-BOYS ARE AWAY, THE ANARCHISTS PLAY” and “KEEP ‘EM IN DOMINICA” (referring to the recent American occupation of the Dominican Republic). The slogans were highly controversial amongst city residents, while appeals to Thorn Grove’s town council to have them stopped (the town having expanded sufficiently to warrant a town council) were unsuccessful. When America did enter the war the following year, Cranford discontinued the signs without comment.

One of the anti-intervention slogans

Over the years, the Baths faced stiff competition from the city’s many saunas, steam houses, Turkish baths, and the Phoenix Medicinal Facilities on Buchanan Street in town (destroyed by arson in 1903; Mr. Cranford was never implicated despite a lengthy inquest), yet it fended off all challengers thanks to Cranford’s keen business sense. A carnival welcomed visiting families and children from the city until 1908, the first women were admitted to the waters in 1919 to celebrate suffrage, and perennial summertime night concerts attracted acts from across the country.

As the economic heyday of the 1920’s rolled in, however, private pools replaced public bathing as the watery standard of conspicuous consumption. The Baths struggled to compete as they declined in popularity—this, despite more frequent night concerts, which even featured a then-unknown Kate Smith. Horse-drawn carriages, the Baths’ staple, were discontinued in 1922 to cut costs. The senior Cranford died at the age of 81 in 1923, insisting on his daily soaking until his final illness confined him to bed. “Perhaps in another lifetime the Creator had fashioned me a fish,” Cranford opined as he approached death. “Perhaps in yet another, I shall return to that form.” His funeral was attended by thousands of the city’s German-American community.

Bankruptcy closed the Baths permanently in 1927, Buckley Cranford Jr. hanged himself in the face of tremendous debt, and the site failed to catch a bidder at public auction. Two decades later, sections of the “Kettle Express” were converted to a freight route for use by Palmer Fisheries. Thorn Grove has thrice successfully resisted municipal annexation, though its charter is up for renewal again in 2011.

Meanwhile, urban expansion caught up with the Baths themselves with the 1962 opening of a pesticides manufacturer upstream and a steady influx of suburban housing developments. The EPA finally condemned the Baths in 1978 when a survey of the East Patterson declared the river’s waters unsafe for swimming. The river passed a later test in 1991, but the Baths remained off-limits, except for occasional night swimmers who would break in for a dip.

In 2004, the well-publicized deaths of David Goldman and Patrick Race, drowned in one such late-night swim, forced Thorn Grove Council officials to act. After a short public consultation which produced such ideas as a mini-mall, a supermarket, a larger mini-mall, and a velodrome, the Council decided not to simply demolish the site as originally intended, but instead to erect a memorial park to nurses of the 1st and 2nd World Wars, incorporating the Baths’ original design.

And so, in a move counter to the region’s recently-acquired penchant for dismantling historic properties (the Park-N-Peek Drive-In Theater in Upper Carsonhurst and No. 18 Antique Row come to mind), a site marked for demolition has caught a significant break. Council Chairman Aaron Hannay will break ground on renovations next Monday, with an intended finish date in the spring of 2009. Plans include a fitness trail surrounding a large quadrangle, a recreation center for children, baseball fields and, happily enough, a swimming pool. As for the baths, the causeway will be reinforced and widened, leading to a single walled-in reflecting pool, a subdued enclave on the former spot of one of the city’s most ostentatious attractions.

– Miles Link

1 comment for “Washed Up? Cranford Baths to be Remodeled”